RICHARD AVEDON "MURALS" AT THE MET

“Richard Avedon: Murals” is currently on exhibition at the Met. Although the exhibition space is small, the images are powerful and visitors leave the space with a perspective on a tumultuous period in American life.

On the entry wall, two photographs flank the exhibition text. The first, a black and white photograph of opera singer Marian Anderson gives a glimpse into the energetic, spontaneous style of Avedon’s early work, which contrasts the stoic murals the exhibition is built around. On the other end of the exhibition text is a self-portrait of Avedon, blankly staring at the camera. Already, the visitor is introduced to the range of Avedon’s photography and the constant experimentation and reinvention he approached portraiture with.

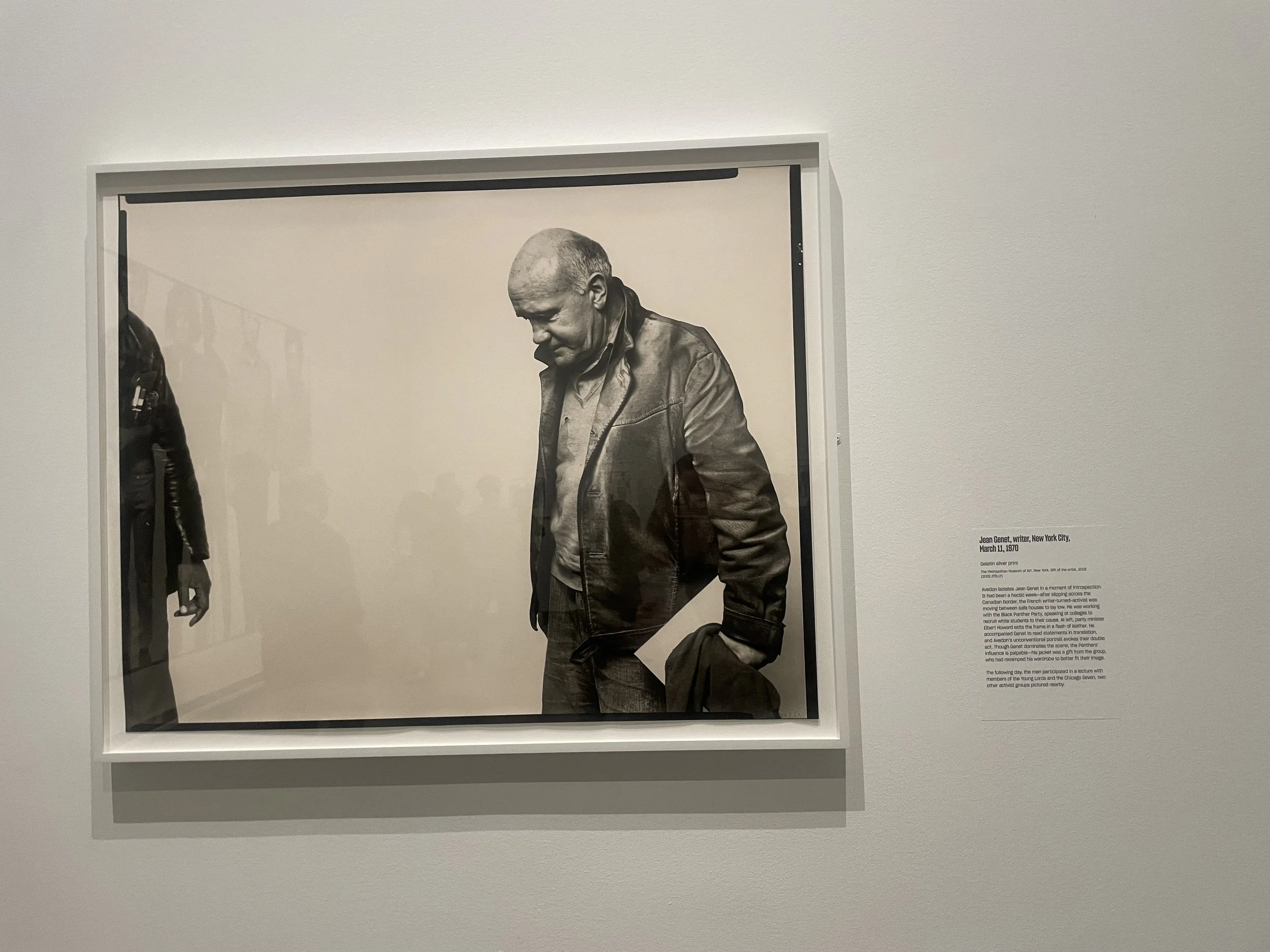

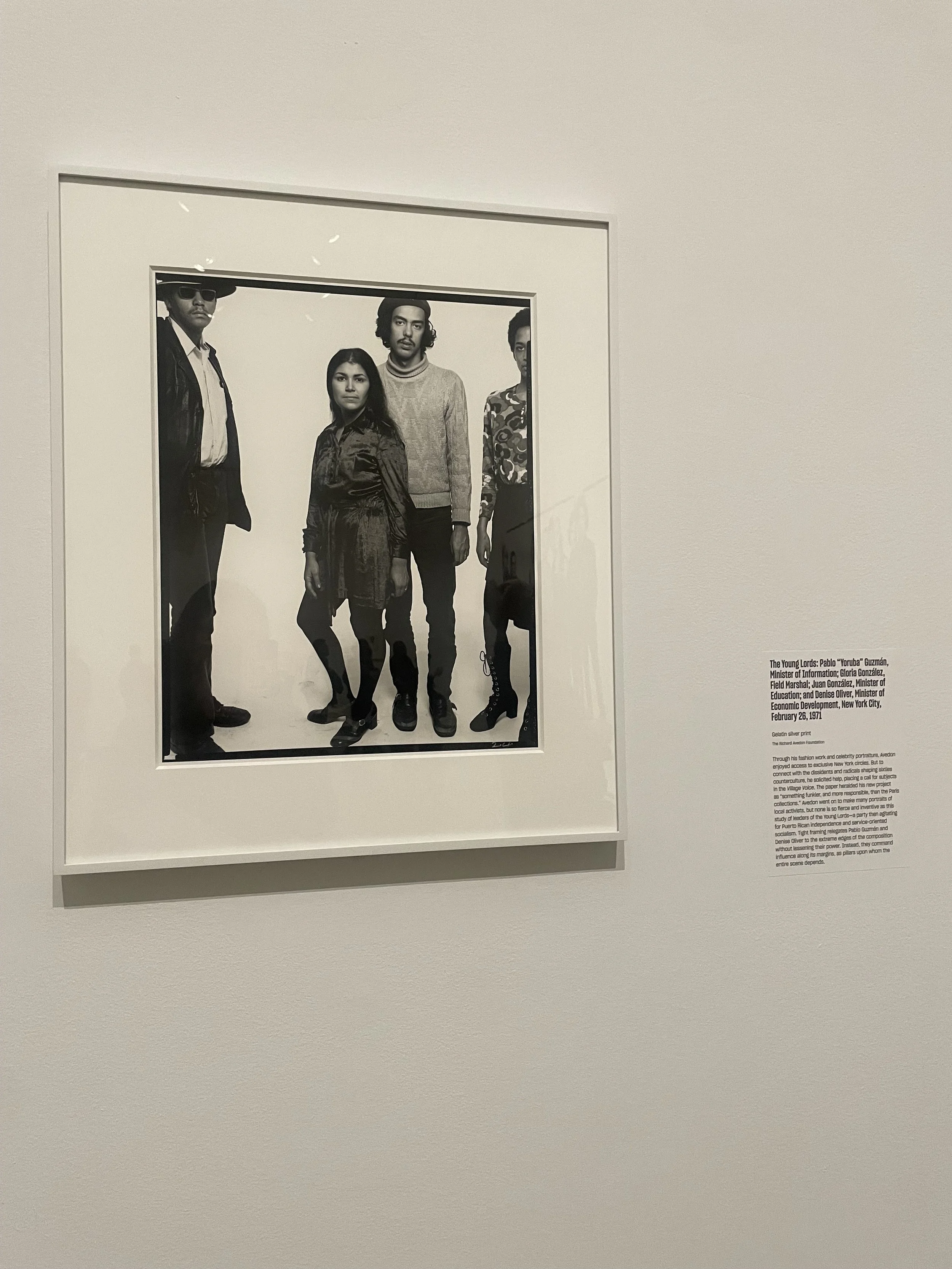

On a wall in the middle of the room are portraits of activists - on one side, the writer Jean Genet who was aligned with the Black Panther Party, on the other, The Young Lords, a party for Puerto Rican independence. These portraits add to the sense that Avedon captured a broad range of society and underpin the politically charged spirit of the exhibition.

The first mural we see is of Andy Warhol and members of the Factory, Warhol’s studio which served as a gathering place for artists and a site for artistic and sexual experimentation and revolution. The mural features actors and creatives such as transgender actress Candy Darling, adult film star Joe Dallesandro, including a group of nude figures, their clothes piled on the ground below them and hanging loosely from their hands, giving the nudity a spontaneous, unscripted quality.

Next to Warhol’s group of sexual revolutionaries is a mural of the Chicago Seven. Originally the Chicago Eight, the group of men were unrelated except for their separate involvement in protests in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The eighth revolutionary, Black Panther cofounder Bobby Seale, whose “outbursts” against his being denied legal representation, self representation, or a continuance in the case led to him being bound and gagged during the trial and sentenced to prison for contempt of court despite his lack of involvement in the demonstrations. He was cut from the court case, and the group became known as the Chicago Seven - however, Avedon reserves a space from him in the photograph. The activists stand rigidly and look directly at the camera, their positioning a reminder that they are separate entitled brought together by the court trial.

The Chicago Seven mural is positioned next to Avedon’s images of Vietnam taken during a 1971 trip to the warzone country for a book he was working on. At the time, he told the New York Times: “My reason for coming to Vietnam is that all the people I have photographed in the last year and a half have been affected by Vietnam—as has all of American life. Vietnam is an extension—oh, unfortunately—of every sick thing in America.”

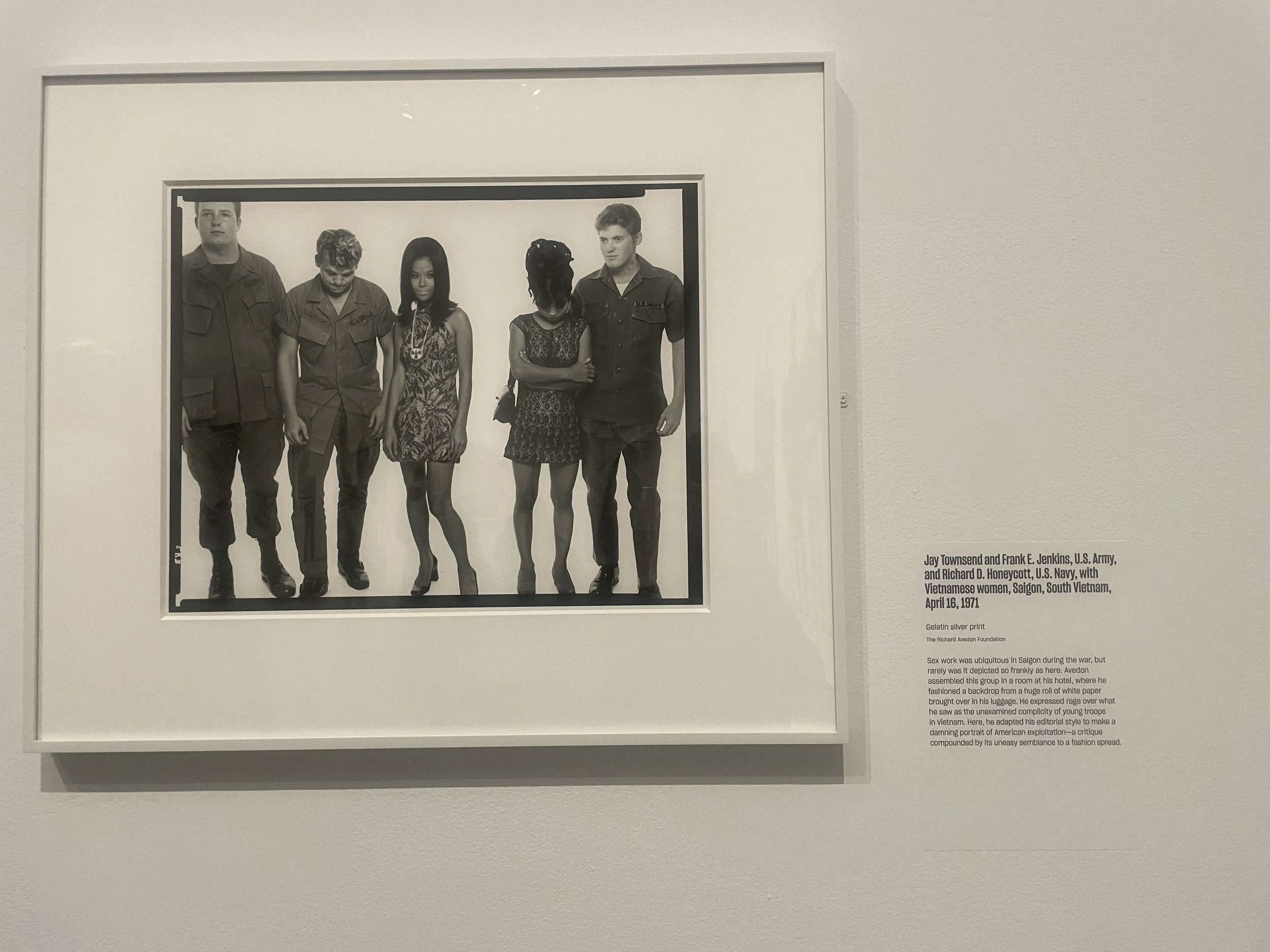

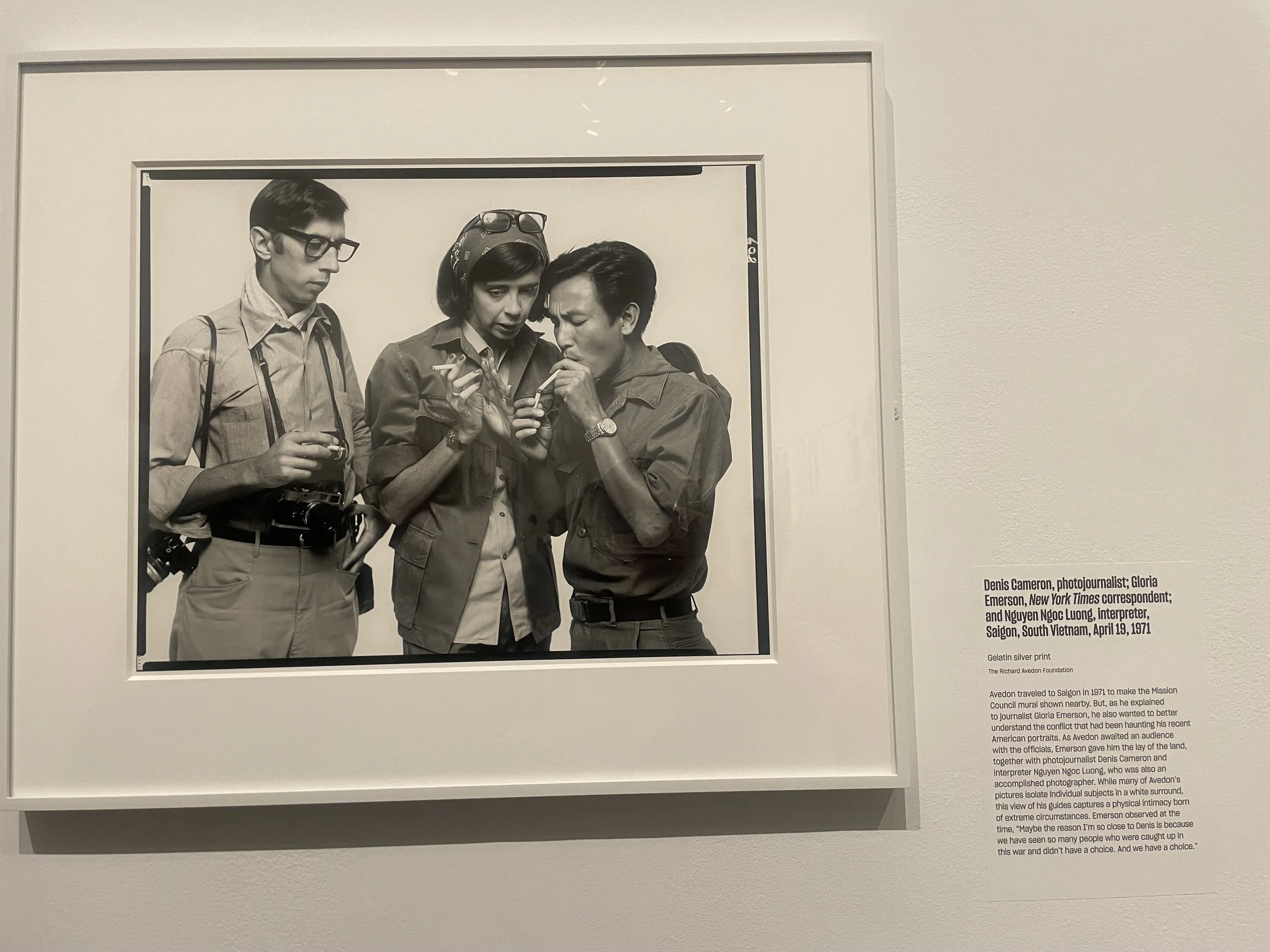

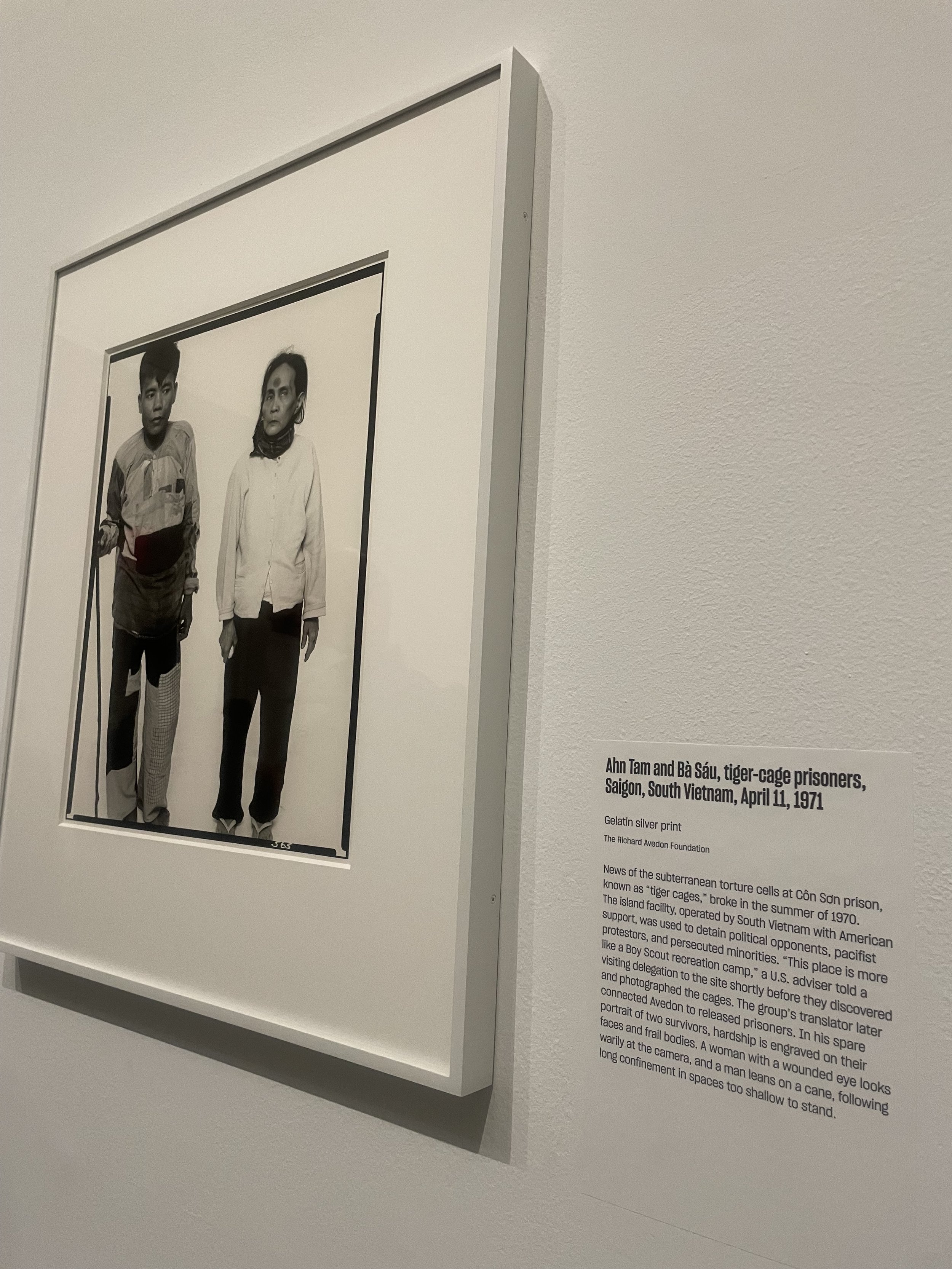

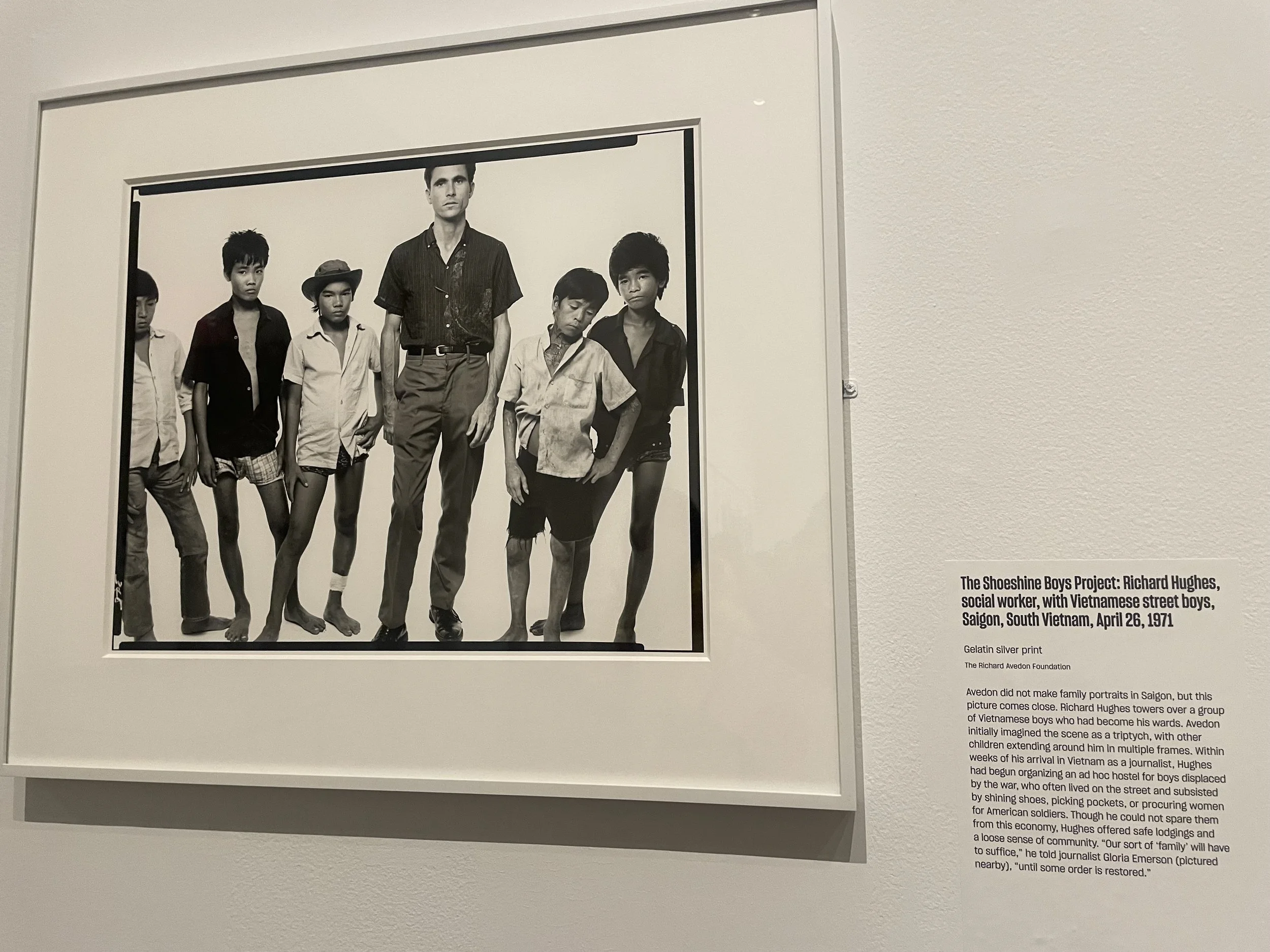

The images from Vietnam ground the mural of the Chicago Seven in the context of what they protested against. In one image, American soldiers are photographed with Vietnamese prostitutes, the men avoiding direct gaze with the camera’s lens, the women “Extraordinary, gentle, direct women and without an ounce of self‐pity,” in Avedon’s words. In another photograph, two released prisoners of the Con Son subterraneaon torture cells appear malnourished and worn down. Another image captures former actor Richard Hughes with the young boys who he took on as wards as part of the Shoeshine Boys Project, in which he offered the “dust of life” street children of Vietnam shelter and food after developing an interest in and desire to aid the activist effort in Vietnam. In another image, American journalists Denis Cameron, Gloria Emerson, and Ngugen Ngoc Luong huddle together.

On the opposite wall of the Chicago Seven, the Mission Council stands with the same stoicism. The group of ambassadors, generals, and policy experts were the architects of the war in Vietnam, and were gathered in South Vietnam. The photograph is organized by rank, with a space open for CIA station chief Ted Shackley, who made an excuse to be absent at the last minute. The significance of the two voids in the murals facing each other is not missed; while Shackley chose not to be in the image, Bobby Seale could not because he was imprisoned.

The Vietnam portion of the room is the most powerful, because it so poignantly maps the players in the Vietnam conflict and the power dynamics at play. Avedon captured those on the ground in Vietnam: the soldiers who were at once symbols of the way American soldiers were victimized by the draft and demands of combat, and perpetrators of violence and exploitation, in this case of the Vietnamese prostitutes, the Vietnamese people exploited and harmed by the American presence, and the Americans who willingly participated in the war as activists. Avedon told the New York Times, “I don't care who they are or what they are doing. We all share something. Every American is in some way using the Vietnamese for themselves‐to build a reputation, to advance a career, to satisfy a need, for something,” a dynamic Avedon and the exhibition invites us to think about.

On either side of the portraits of those in Vietnam are the parties involved from afar; on one side, those orchestrating the war, on the other, those opposing it. The former, a highly protected group of men, on the other, a group of men facing imprisonment, both of them recognizable public figures in this period of American history, standing at opposing ends of an all-consuming current event.

The exhibition is powerful precisely because it strips bare the political and cultural figures at play in the 1970’s. Avedon’s stark aesthetic equals the playing field, giving the same weight to government officials and the activists who oppose them, prostitutes and soldiers, Vietnamese children and Americans abroad. At the same time, his fashion-informed eye sensationalizes these characters, making them feel larger-than-life. The visitor leaves with a small insight into how tumultuous and confusing and charged the time period was, viewing the icons that influenced the country and the world at that time as contemporaries rather than relics of the past.

The exhibition also serves as proof that fashion photography is not just the stuff of glossy magazines and glamor shots, but a lens which sharpens our perspective. The combination of planning and spontaneity with fashion photography’s need to be captivating, innovative, and timeless makes it a vehicle for simplifying and defining the character of people and an era. Avedon’s murals are not a departure from fashion, but an embrace of it, a demonstration of how fashion photography allows us to see the world more sharply.