SCULPTURE OF THE LENS

December 15, 2021 - January 09, 2022

“Why talk about sculpture when I can photograph it?”

Sculpture and photography are perhaps often thought of as opposing mediums that inhabit disparate worlds. Sculpture is one of the earliest and most traditional forms of art, a medium historically considered to be refined and well respected by the canon. Photography, on the contrary, is associated with the new, the modern, the digital and today it has even become a part of our daily existence. In searching for intersections between these two distinct mediums lies the world of Fashion Photography; a world consistently craving for what comes next, an accessible art form bound not by institutional walls but by your everyday magazines, and yet a medium that has always embodied a sense of refinement and that lies among the finer things with a keen eye for beauty.

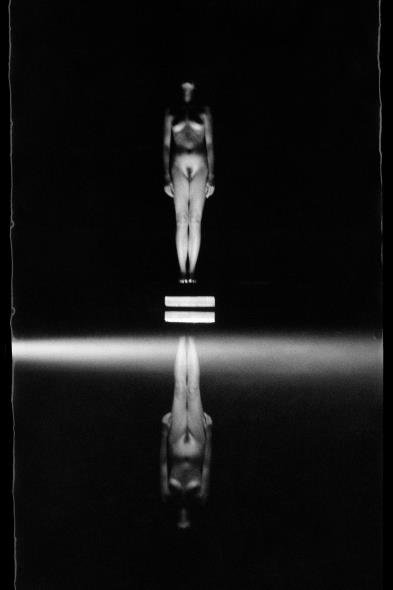

The photographs displayed in this exhibition possess sculptural qualities, with poised figures and tensed muscles they emulate visions of Ancient Greek and Neoclassical statues. These works capture elements of stillness and motion at once, portraying the human body in a myriad of configurations, as both flesh and stone, converted through the eyes of the lens.

SCULPTURE OF THE LENS: HISTORICAL INFLUENCES OF SCULPTURE IN CONTEMPORARY FASHION PHOTOGRAPHY

Historically, sculpture was long regarded as one of the pinnacles of art, a highly technically skilled medium and most engaging to the senses in its appeal to the three-dimensional desires of the human eye. Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), who is often referred to as the father of art history, a title which comes with many biases like Vasari himself, wrote his treatise Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects in 1550 which predicted that painting, sculpture, and architecture were the three most refined and significant forms of art. Vasari’s opinions were widely disseminated and permeate even today into the foundations of how art is understood in Western culture. It is therefore no surprise that the advent of photography was less than welcomed into the category of the fine arts, a medium born from modernity, the antithesis of sculpture’s ancient origins. As cultural and artistic movements continued to grow, photography developed into an ever changing medium, pioneered by the likes of Man Ray, Claude Cahun and Lee Miller and with the evolution of fashion photography came the works of Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Lillian Bassman, David Bailey, Helmut Newton, Chris von Wangenheim and Sarah Moon to name a few.

Although the mediums of classical sculpture and contemporary fashion photography may seem disparate, the two have a common desire to create art with a sense of refinement, and share a keen eye for detail, or often even perfection. These intersections are illuminated when viewing specific works.

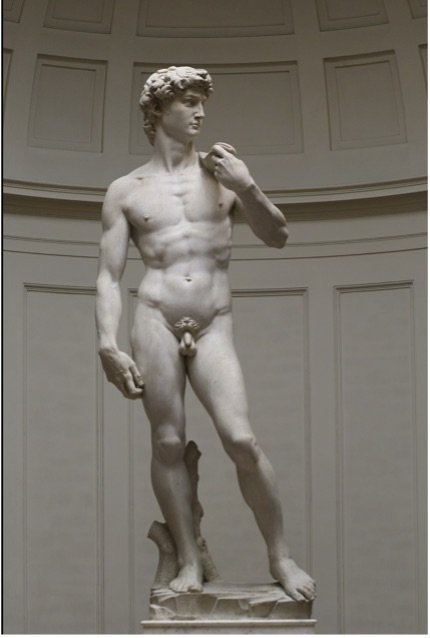

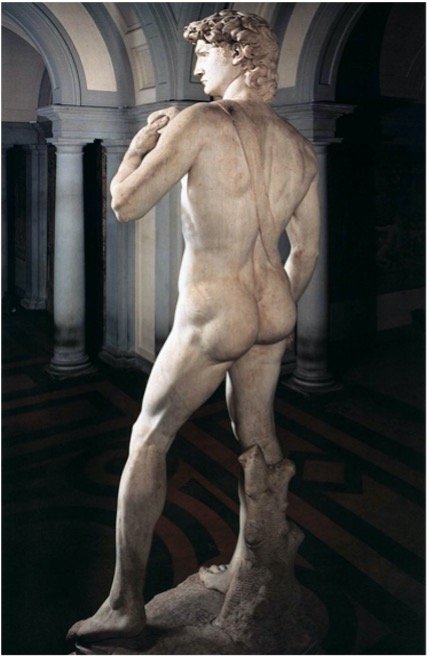

Looking at the focal image of the Sculpture of the Lens exhibition, Richard Phibbs, Gonzalo’s Legs, New York City Ballet, 2013 and perhaps one of the most famous neoclassical sculptures to date, Michelangelo's David, 1501-1504 there are clear comparisons to be made. The resemblances between the two are evident in the rendering of the toned muscular legs, the strong sense of weight and balance, and even the white ballet tights which create the impression of smooth white marble. Like Michelangelo’s David, Phibbs’ photography highlights the ultimate athletic male physique with grace and poise rather than brute force. There is much more than can be said about this but in short, the two both present altered versions of masculinity in their works, perhaps a challenge to societal norms.

The works of Phibbs are innately sculptural as he takes sharp focus on the human form, highlighting every muscle, wrinkle, and line, capturing the human body frozen in time and in movement. This is perhaps why many of Michelangelo’s sculptural works can be seen mirrored and taking on a new life in Phibbs’ works, whether these references are intentional or not. Phibbs’ Waterpolo I, Los Angeles, 2008 and Untitled, 2008 appear visually in tune with Michelangelo’s relief entitled Battle of the Centaurs, 1490-1492. The two works, image and sculpture, fuse together human forms, creating entangled bodies and blurred shapes that somehow remain to intricately display their muscles in detail. Both works present a moment of intensity and appear to press

pause on a moment of extreme tension as each body pushes and pulls against the next.

The Ancient Greek sculptures which inspired neoclassical sculpture can also be found clearly referenced in fashion photography. The works of Giovanni Gastel draw on themes of beautiful realities existing only in dreams, often referencing classical literature and theatre. Gastel’s photographs entitled Fallen Angel 22 and Fallen Angel 24 from his 2015 series Fallen Angels strike a clear resemblance to The Winged Victory of Samothrace c. 200-190 BC, one of the greatest treasures of the Louvre Museum, Paris. The feathered wings and flowing white fabric draped over the body highlighting its curvature create a soft visual likeness. However, whilst the classical sculptural figure is in a moment of momentum, as she is about to take flight, Gastel’s angels are instead falling weightlessly from the sky.

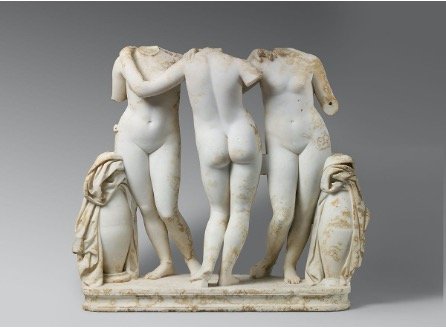

Parallels can also be drawn between imagery of The Three Graces from Ancient Greek mythology and Robert Farber’s, Lingerie, 1977. The classic beauty of the women and flowing white garments draped over their posed bodies creates a gentle resemblance to the sculpted women. Further influences can be seen in the carefully choreographed poses of Farber’s models, which align perfectly with the arrangement of the Three Graces. The second and central woman faces away from the viewer with her back turned whilst her arm is outstretched, almost lining up with the shoulder of the model to her left, following the familiar arrangement in classical imagery.

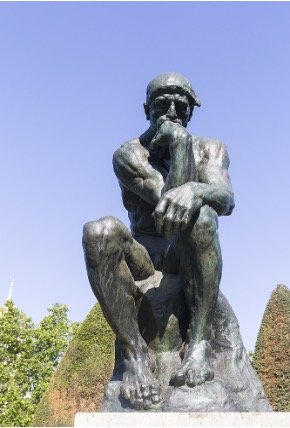

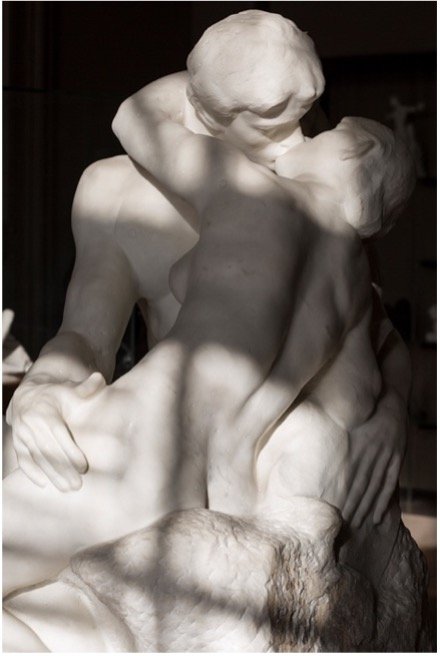

Moving into the 19th and early 20th century of the Modern period, and into the world of one of the most famous French sculptors, Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). There are echoes of Rodin’s The Thinker, 1904 and The Kiss, 1888-1898 in the works of Paul Bellaart; The Thinker, 2016 and Untitled, 2016. While perhaps Bellaart’s thinker presents a delicate female nude rather than a roughly chiseled man, the pose and title are clear influences, and the two works share a mutual tone of stillness and contemplation. Bellaart’s entangled lovers in Untitled share a striking resemblance to Rodin’s Kiss, the two works capture an intimate moment of love and trust, in both, the softness of the human form and its flesh is palpable.