The Getty Museum’s first AI photograph acquisition: a radical departure or photography’s next chapter?

Museums began acquiring photography as early as the 19th century, but sustained institutional interest in fashion photography did not emerge until the 20th century—most notably in the 1930s, when the medium gained recognition as a legitimate art form. This shift led to the establishment of dedicated departments and gallery spaces, which played a pivotal role in elevating photography’s cultural standing. Since then, the appetite for photographic works—particularly within fashion—has continued to intensify, and museums today remain committed to expanding their photography collections, affirming the medium’s evolution and its capacity to welcome new artistic voices.

As these collections broaden, so too does the willingness to embrace emerging modes of image-making, including the use of artificial intelligence. It is within this evolving context that Cristian en el Amor de Calle has drawn particular attention—and debate—due to its incorporation of AI. Earlier this year, the Getty Museum acquired the piece for inclusion in its February exhibition The Queer Lens. The work is by queer Costa Rican artist Matías Sauter Morera.

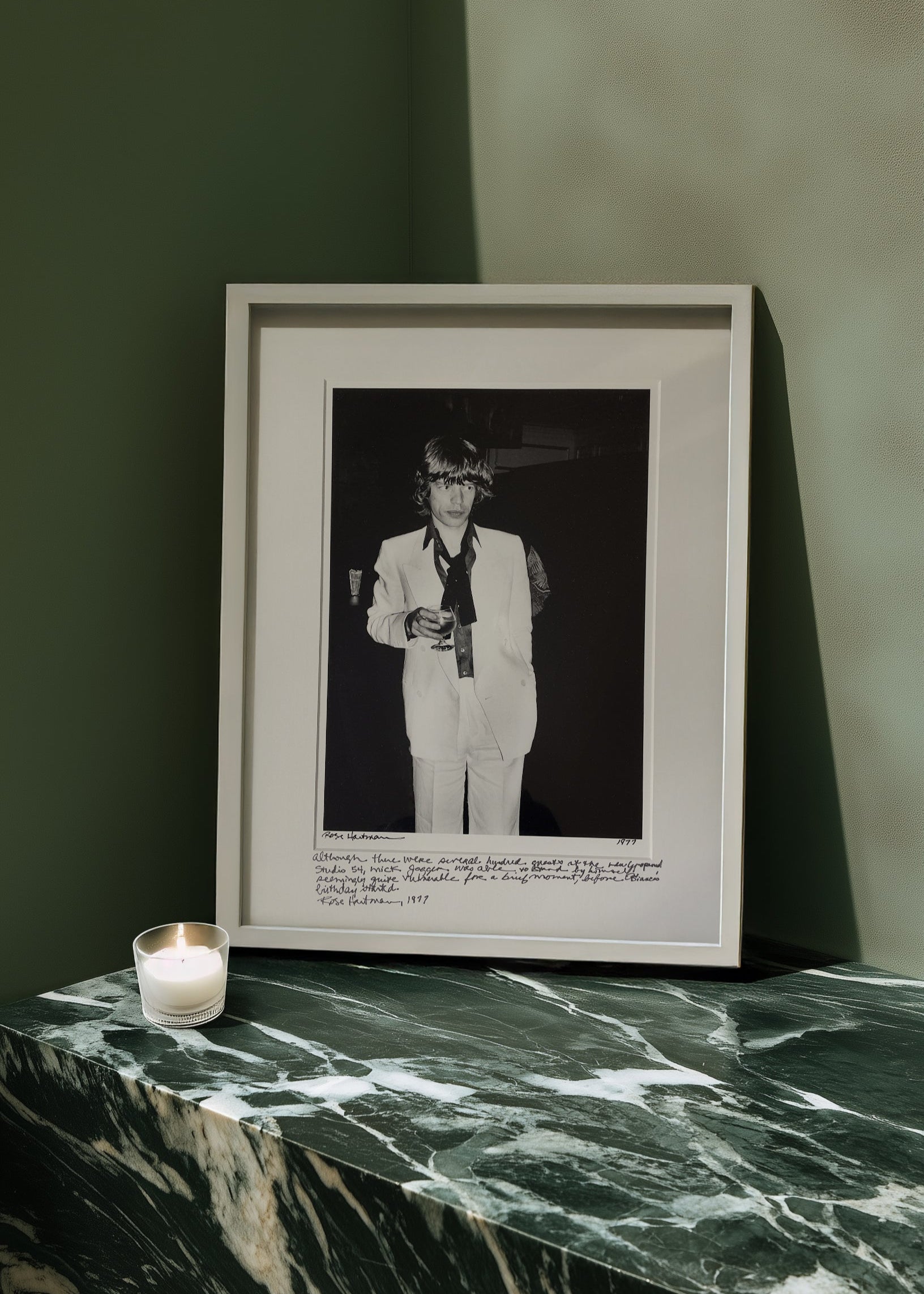

Matias Sauter Morera. Cristian en el Amor de Calle (2024). Photo courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery

The photograph reflects the queer history of Costa Rica during the 1970s, drawing on the stories of the pegamachos—cowboys from the Guanacaste Coast who discreetly formed relationships with young gay men in the region. While traces of this hidden way of life persist today, they remain largely unseen, operating quietly in the shadows. In the image, two young men sit in a sun-worn yellow room, their stares sharp enough to pull the viewer inward. One confronts the lens in perfect clarity; the other hovers just beyond it, softened at the edges like a memory. Draped in electric-blue leather jackets embroidered with glints of gold, they radiate a bold, almost cinematic presence. Their jet-black hair lifts into loosely formed pompadours, recalling Elvis while suggesting a grittier, more unrefined contemporary edge.

Matias Sauter Morera, Untitled (from the Barbie Town parties portrait series, 2024). Photo courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery

Matias Sauter Morera, Untitled (from the Barbie Town parties portrait series, 2024). Photo courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery

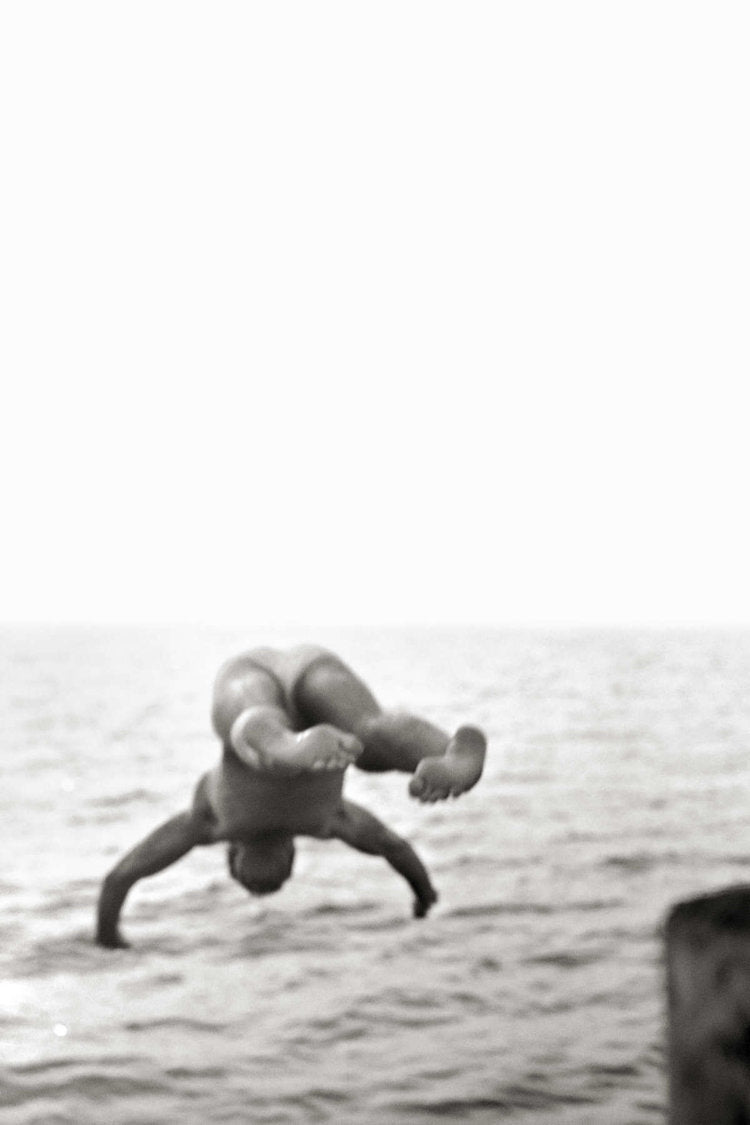

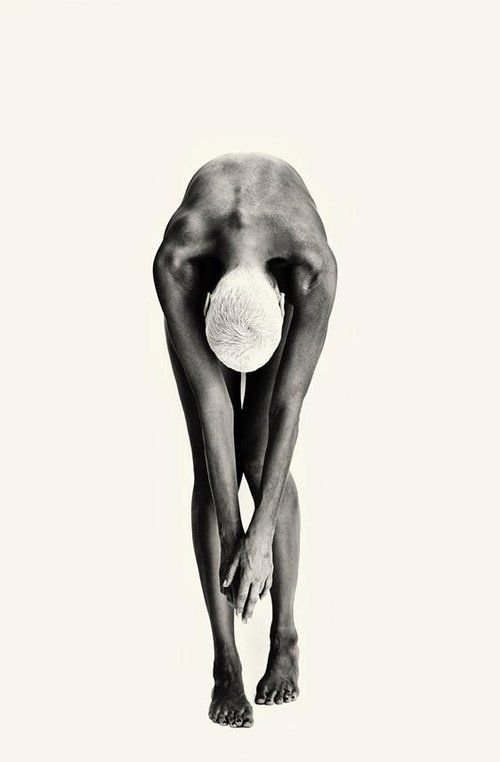

To construct these images, Matías employs AI alongside Photoshop—a deliberate, not convenient, choice rooted in the need to protect the anonymity of individuals within an already discreet community. By generating imagined figures to inhabit realistic scenes, the work becomes a ghostly mimicry of photography, echoing the medium’s visual language while shielding the people whose stories inform it. While some debate the legitimacy of AI as a photographic tool, such concerns overlook a long tradition of technical evolution within the medium: from albumen prints to salt prints, from analog to digital, photography has always adapted to new technologies. AI is simply the latest step in this continuum. Controversial as it may be, it remains anchored in the same core pursuit—using evolving tools to create images that speak to human experience.

Matias Sauter Morera, Miguelito, (2024). Photo courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery

Matías’s work embodies photography’s enduring mission: to reveal what is overlooked and to restore humanity to the unseen. It recalls Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, which exposed the struggles of migrant families in Nipomo, California during the Great Depression, as well as the iconic Napalm Girl from Trảng Bàng in the Vietnam War—a photograph still surrounded by questions of authorship. Like these powerful images, Matías’s work confronts themes of invisibility, suffering, and endurance, yet it diverges in approach: rather than documenting reality, his compositions are deliberately staged, offering cultural insight through constructed scenes. In this way, his photography reminds us that the medium’s greatest strength lies not only in recording the world, but in deepening our empathy and connection to the human experience.

Matias Sauter Morera, Leyenda (2024). Photo courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery

Matias Sauter Morera, Armando despues de un aguacero (2024). Photo courtesy of Craig Krull Gallery

In many ways, the work also prompts the museum to reconsider where it belongs: alongside traditional photographs or within emerging digital-art spaces. Wherever it is ultimately housed, Matías’s intentional use of AI undeniably expands the medium’s conceptual reach. Though it does not extend photography’s technical lineage, the piece opens new avenues for grappling with memory, imagination, and overlooked histories—showing how the medium continues to evolve at the intersection of technology and artistic vision. Beyond its technological intrigue, this acquisition also nudges the museum toward broader cultural representation; in a collection long dominated by Euro-American photography, it brings forward missing stories and allows the institution to more fully reflect the diversity of photographic experience. In doing so, it helps reframe photographic history itself, signaling a shift that may inspire similar change in other institutions over time.

READ MORE BLOGS